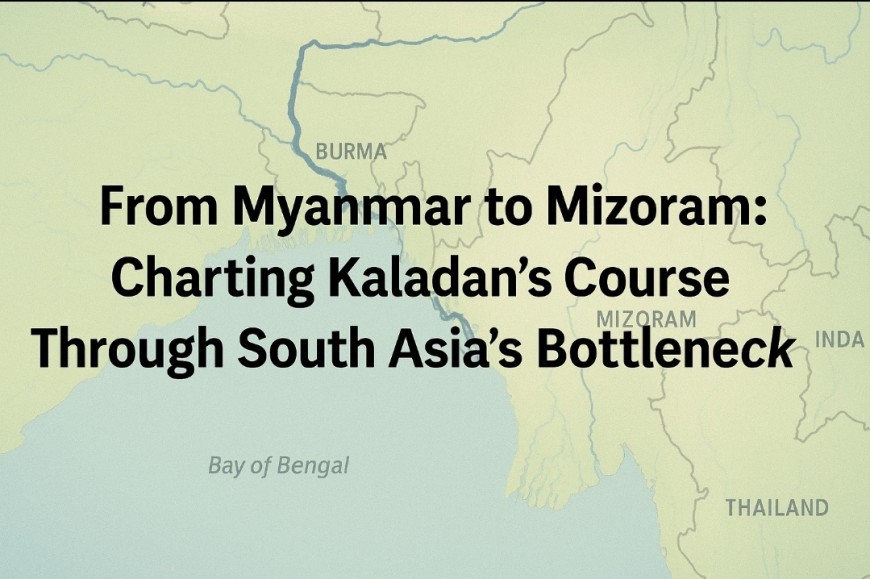

From Myanmar to Mizoram: Charting Kaladan’s Course Through South Asia’s Bottleneck

India’s northeast: home to 45 million people across seven states, is effectively land-locked by a narrow stretch of plains and its international borders. Geography has long been a hurdle, but geopolitics compounds the challenge: trade routes, energy supplies, and even national security hinge on a handful of fragile corridors.

This May, two developments have propelled the region into the strategic spotlight. First, New Delhi has fast-tracked progress on the US $484 million Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, promising an alternative lifeline into Mizoram. Second, Assam’s chief minister ignited a social-media skirmish with a pointed warning about Bangladesh’s own “chicken necks.”

Together, these moves underscore what’s at stake: not just commerce and connectivity, but the very trust between neighbours in South Asia.

Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Project

Conceived under India’s “Look East” policy, the Kaladan project aims to link Kolkata by sea to Sittwe port in Myanmar, then push inland via the 158 km Kaladan River waterway to Paletwa, and finally by road over 109 km into India’s Zorinpui border crossing. Launched in 2013 with a target completion date of 2019, it has been dogged by land-acquisition delays, monsoon-woven dredging challenges, and security setbacks.

Yet this May, six new barges plied the river, the port’s handling capacity has doubled, and over three-quarters of the Paletwa - Zorinpui highway is under advanced construction. If delivered on its current accelerated timetable, Kaladan will slash the Kolkata - Mizoram haul by more than 1,300 km, opening a true second gateway to India’s northeast.

Bypassing the “Chicken Neck”

For decades, the Siliguri Corridor: barely 22 km wide at its narrowest, has been the region’s Achilles’ heel. A single landslide, political standoff, or security breach can sever the lifeline to five northeastern states. By providing an alternate route through Myanmar, Kaladan mitigates dependence on Bangladesh permissions and reduces transit times dramatically.

The Kaladan project’s momentum leapt forward this May, driven as much by geopolitics as by engineering. In March, Bangladesh’s interim chief adviser Muhammad Yunus declared his country “the only guardian of the ocean” for India’s land-locked northeast. A barb that sparked alarm in New Delhi India Today.

Within weeks, former Mizoram CM Zoramthanga revealed that the Centre had fast-tracked dredging and road-building to counter any threat to the Siliguri corridor, moving Kaladan’s completion target up by two years The Times of India.

On the ground, this urgency translated into round-the-clock work: rivers cleared of silt in record time, six more barges deployed on the Kaladan, and contractors racing to seal the final 25 km of highway before monsoon rains.

Assam’s Retort: Two Chicken Necks of Bangladesh

On May 25, Assam CM Himanta Biswa Sarma took to X to fire back: “Bangladesh has two of its own ‘chicken necks’: both far more vulnerable than ours” Business Standard. He mapped the 80 km Dakshin Dinajpur–South West Garo Hills corridor and the 28 km Chittagong–Tripura link as pinch-points that could sever Bangladesh internally.

By reframing vulnerability as mutual, Sarma shifted the narrative from India’s sole exposure to a shared geographic squeeze. In Dhaka, official channels remained muted, but social media buzzed with analysts debating which country truly held the dice.

Sarma’s “two chicken necks” salvo has injected fresh tension into India–Bangladesh relations, already strained by China’s expanding footprint via BRI projects The Week. Dhaka’s foreign ministry has yet to issue a formal protest, preferring private demarches over public recrimination; meanwhile, Bangladeshi editors deride the spat as “geographical trivia” unworthy of statecraft.

Yet the timing is critical: bilateral talks on transit rights and cross-border trade, slated for June, now risk being overshadowed by rhetoric. With every public jab, New Delhi and Dhaka edge further from the cooperative connectivity agenda that both sides once championed.

Beyond logistics, the project carries strategic weight: it softens the leverage that any single neighbour might wield over India’s northeastern flank, cementing a more resilient supply chain and reinforcing New Delhi’s Act East ambitions.

Economic Stakes: Trade, Tourism, and Connectivity

Kaladan is as much an economic lifeline as a security corridor. Once fully operational, Sittwe port has the capacity to handle 40,000-ton vessels, and since May 2023 has processed over 109,000 tonnes of cargo… ranging from construction steel to consumer goods, underscoring its budding trade potential ORF Online.

For Mizoram, known for its fragrant tea estates, vast bamboo groves, and untapped eco-tourism along lush river valleys, this new route promises lower logistics costs and faster market access. Cargoes of Mizo tea and bamboo can move directly to global buyers via the Bay of Bengal, while adventure seekers may swap the Siliguri slog for a scenic boat ride through Myanmar.

Moreover, Kaladan dovetails with broader regional plans… from the once-hyped BCIM Economic Corridor connecting Kunming to Kolkata European Parliament, to the BIMSTEC Transport Master Plan, which envisions multi-modal links between India, Myanmar, and Southeast Asian partners ORF Online. Together, these frameworks could transform South Asia’s economic geography.

The Larger Strategic Picture

Kaladan sits at the centre of a wider chessboard. China’s “String of Pearls” strategy. dotted with ports and facilities in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, is designed to secure Beijing’s sea-lines of communication and encircle India Wikipedia.

In response, New Delhi has rolled out the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, accelerated the India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway, and doubled down on its Act East diplomacy to knit its northeast more tightly into ASEAN markets East Asia Forum.

Yet while politicians trade “chicken-neck” barbs, the reality is far more interdependent: Bangladesh, India, and Myanmar share rivers, roads, and markets that no single corridor dispute can truly sever.

Delhi now faces two tests: deliver Kaladan on time and manage diplomatic optics with Dhaka and Naypyidaw. If successful, the northeast gains a new economic artery, and Bangladesh can shift from reluctant gatekeeper to cooperative partner.

But if delays persist or tensions flare, both India’s Siliguri squeeze and Bangladesh’s own pinch-points loom larger, exposing South Asia to fresh strategic shocks. In this high-stakes game of geography, infrastructure must become the cement of confidence, not just the scaffold of strategy.

What's Your Reaction?